The house is a talisman – all of it – built circa 1915 in the Rosebank section of Staten Island, bought by my parents in 1948 for ten grand (a stretch for them, then), wood-framed and cedar-shingled (shingled, that is, until they cocooned it in tawny aluminum circa 1970). The two-floor, three-and-a-half bedroom, one-bathroom house on St. John’s Avenue sits a few blocks inland and uphill from the Narrows. In the winter when the trees are bare, you can see the Verrazzano bridge to Brooklyn from one bedroom window and the skyline of lower Manhattan, farther off, from another. When I looked out those windows as a kid, I felt reassured. I knew that I could get away. And I did leave at seventeen, never expecting to sleep under this roof on this island again if I could help it. And here I am at sixty-five, taking in the views.

Mom lived in this house until she died, or a few weeks before she died to be exact. It was 2014 and she was a hundred and three years of age. She lived here on her own for more than thirty years after we lost dad. Near the end she had a fall and broke her femur. She died in her sleep in a nursing home where she was on the mend and pining to get back to St. John’s Avenue.

I was living and working in Rome at the time but knew I would be coming back before long and would need somewhere to land. Keeping the house just made sense, even though I had never remotely considered it before. So I took out a loan and bought out my three siblings’ shares. My barely grownup son moved in to caretake the empty place, its decades of familial detritus mostly cleared out or sold off. The following year, I came home. Yes, I moved directly from the Esquiline hill in Rome to the northeastern shore of Staten Island. Not many people can say that except for some Italian immigrants, and most of them are long dead.

When I moved in, I needed to make some changes, not really to exorcize any spirits, which if present posed no clear danger, but just to call the house my own. The renovations were mostly superficial; I wanted to paint the walls in bold colors and assert myself. First, however, I had to strip out all of my parents’ (well, really my mother’s) flowered and filigreed mid-century wallpaper, which in any case was beginning to peel away with age. In the process, in my old room – I got the half bedroom, fate of the youngest born – the top layers came off to reveal another pattern, faded but intact, dating from the early 1960s.

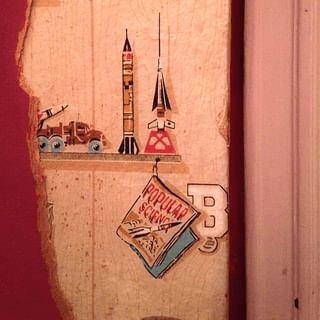

The re-exposed wallpaper of my childhood depicted a cartoony, Space Age scene of toy rockets and toy jets and toy army trucks carrying little missiles ready to launch. I had no conscious memory of that cutesy Cold War imagery until the moment I saw it again, and then the synapses sparked and the memory came rushing back. I remembered it instantly, and I remembered how much I liked it. There it was, that indulgence for the son born when mom was forty-seven, the miracle baby sent by Jesus to ease the pain of losing another child in infancy a few years before, the sister I never knew who my parents named Grace. This is what I gave them, I suppose, through no fault or intention of my own: one last chance to fill that room.

Lately I’ve been thinking about selling the house, though I doubt that I will, at least not yet. My son lived here with me until about a year and a half ago when he moved into a different house with his girlfriend. These days I can’t deny that I have more space than I need. Still, I love the place. Even if it is on Staten Island, it has good bones as they say, and it’s not expensive. But I don’t want to become my mother and fear that I might if I stay. One thing is certain: I would not want to live as long as she did. Nobody should, really. It’s not healthy. Nevertheless, sometimes letting go is hard.

Addenda

Since posting this piece, I have discovered the story of another house on Staten Island and another family. This story says more about the social dynamics of the place in the decades before my birth, specifically its legacy of deep racial animus as what was and remains New York City’s whitest borough. Below are two downloadable PDFs: a detailed essay about the house at 167 Fairview Avenue and its late owners, Samuel and Catherine Browne; and the script for a proposed documentary comic book about their struggle.

Standoff on Fairview Avenue: Resisting racial hatred and housing discrimination on Staten Island in the 1920s [research paper]

Standoff on Fairview Avenue [script]