For some reason – in my experience, at least – coincidence and simultaneity tend to arise in the context of travel. There’s something about being unmoored from everyday routine that charges the particles of your personal universe with extra voltage. Perhaps because they are vibrating at a slightly higher frequency than usual, unlikely intersections of time and space ensue.

Of course, some minor coincidences arise naturally, like running into your Delta Airlines seatmate from Newark on the streets of both Rome and Florence because your itineraries overlap and you’re both doing the same kinds of touristy things. But then there are more random, less rationally explicable cases.

One of these occurred when I traveled to Ireland in August of 1980. Midway through the trip, I happened to meet another young American at a roadside on the Dingle Peninsula, against the backdrop of the country’s gorgeously craggy Atlantic coast. In a conversation spanning no more than five minutes, he and I shared a smoke and a few travel tips. We also bonded over our frustration with hitchhiking in a place where – at that time, anyway – large families were still the norm and cars were often crammed full of kids, while those that did stop were seldom going farther than the next town. We did not discuss where we were from. I don’t think we even exchanged first names. Then each of us went his own way, in two different directions.

About three weeks later, I was back in Albany, New York, where I lived at the time, having a beer at my local bar, the Washington Tavern, when this same young man walked through the door with a couple of his friends. We locked eyes and froze for a moment of disbelief morphing into recognition, and then we both burst out laughing. It so happened that we lived a few blocks apart and frequented the WT (as regulars called it), though we had never met. For another five minutes or so, we marveled at the happenstance of our twin encounters in Dingle and now, much more prosaically, Albany. The only common thread we could conjure was that an Irishman who had immigrated from the west of Ireland owned the WT. In fact, I worked there part-time, and he was my boss. Once we had exhausted that topic, however, we quickly realized that we really had nothing else to talk about. He returned to his friends and I returned to my beer, and that was it. But I have never forgotten the momentary jolt of wonder I felt that day in Albany.

I took several more trips abroad in the following years, including a month-long Spanish foray with my girlfriend in the mid-1980s. We flew into Madrid and originally planned to backpack around, but when we got to Barcelona, it was so entrancing that we decided to stay put there. This was not the globalized, cosmopolitan city that Barcelona has become. It was the more traditional, old world, Catalan capital that existed before it was transformed by massive investment in the 1992 Olympics and, later, Spain’s accession into the E.U. It was a city of full-menu lunches with carafes of vino tinto for the equivalent of three dollars, of Roma women dressed in black (we called them gypsies then) hustling palm readings and casting sharp over-the-shoulder glances if you turned them down. Rachel and I had decided to spend most of each day exploring the streets and plazas separately, then meeting up for a siesta and going out for a customarily late Spanish dinner in the evening. Something about this balance of solitude and togetherness helped us savor the taste and smell and sound and even the heat of Barcelona that summer.

It was on one of my solo daily walks that the incident occurred. I would not call it a coincidence, exactly. It was more of a simultaneity of feeling, a telepathic connection, a long-distance stab of grief. And as hackneyed and pseudo-mystical as this sounds, it started with a Tarot card.

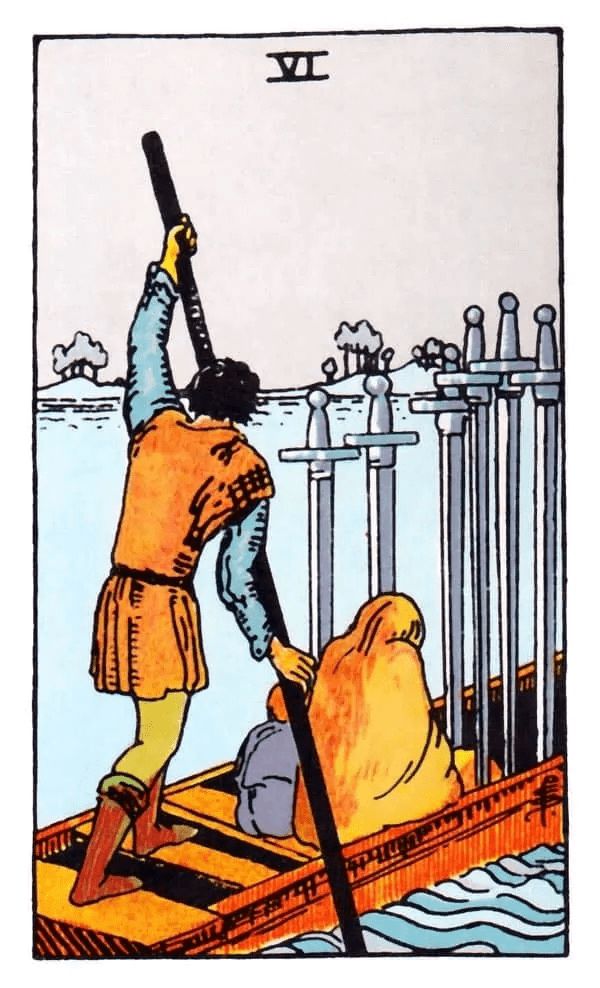

I was on my way that afternoon to the Sagrada Familia, the Gothic and Art Nouveau basilica, still unfinished then as now, which obsessed me with its cluster of sensuous curvilinear steeples. I liked to pass by the church each day and view it from different angles. I had never seen a stone structure that looked so organic, like a giant creature poised to leap across stately avenues. The church was still at some distance when I spotted the card on the cobblestones just ahead. I didn’t know much about the Tarot then – I still don’t – but the small rectangle of color popped against the grey pavement and caught my eye. On a whim, I picked up the card and examined it briefly. It was (I know now, because I have looked it up) the Six of Swords, and I held it upside-down for a moment before rotating it to examine the figures depicted on its face: a boatman standing like a gondolier behind a seated mother and child, pushing their boat forward with a pole. All three figures had their backs to the viewer and faced six large swords in the bow.

I didn’t know what to make of this find, but I know now (because I have looked this up as well) that the Six of Swords upside-down can spell trouble, if you subscribe to that sort of thing. And so, without giving it much thought, I slipped the card into the breast pocket of my shirt – a souvenir from my wanderings, which I could show to Rachel later on – and continued on my way. A few minutes after that, I approached the Sagrada Familia. But instead of my usual pleasure in observing this glorious pile, I felt a vague tug of anxiety in my stomach. I noticed, too, that I was sweating even more than the July sun warranted. I kept walking but decided to head back in the direction of the small hotel where we were staying. Maybe I’m getting sick, I thought. I must have had too much wine at lunch. As I navigated the narrow streets, I also had a creeping urge to phone home – that is, to call my mother at our family home on Staten Island. Why, I had no idea. I generally did not check in with mom by telephone from abroad in those days, partly because, before the advent of mobile phones, this could be an expensive proposition involving complicated connections over intercontinental trunk lines. Instead, I usually took the cheaper, easier option of sending occasional postcards, even though they might not arrive in the States before I did. Still, the urge to call intensified with every step.

My mother lived alone then, in her seventies, for the first time in her life. My father had died unexpectedly of a heart attack in 1981, after my siblings and I were all out of the house. It was a tough transition for her after thirty-six years of marriage, but she was soldiering on. In fact, she wasn’t completely on her own. She had company in the form of Dusty, a big, sloppily friendly German Shepherd mix we had adopted when I was a teenager. After dad’s death, mom lavished Dusty with surplus affection during otherwise too-quiet days and nights. Under the circumstances, she was doing pretty well, and I did not worry about her very much. Thus I was confused by my sudden desire – no, urgent need – to check in with her. It took a while before I came across a phone booth. I finally found one in a quiet plaza. By that time, I was beginning to tremble. After contacting an overseas operator, I struggled to insert the requisite ransom of pesetas and the call went through.

“Hello?” my mother said, her voice disembodied and hoarse.

“Hi mom, it’s me. Is everything … okay?” I stumbled, surprising myself with the question. Silence rose through the static of a transatlantic cable. “It’s me.”

“I know who it is,” she answered. “I haven’t heard from you for so long. Why are you calling? Why today?” Her words were clipped as if in anger or hurt.

“I don’t know. I just wanted to see how you were.” More silence followed, broken by what sounded like a muffled sob.

“Not good,” she said at last, and I could hear the raw emotion now. “Dusty died yesterday. I wanted to tell you, but I didn’t know how … how to get in touch with you.” In tears, she went on to tell me the story: that Dusty was acting lethargic and had blood in her stool, that my mother had planned to take her to the vet the next day but, hours later, found her still and cold to the touch. As I listened and commiserated, I ached for mom having lost not just a pet but a living link to her lost husband and a precious object of unconditional love. It must have felt to her like the waning of joy in her life, irretrievable, final. It felt that way to me, too. I did my best to comfort her at such a distance, haltingly and unsuccessfully. In a few minutes, my pesetas ran out and I had to say goodbye.

Emerging from the phone booth into the plaza, I remembered the Tarot card in my pocket. I’m sure it is a trick of memory, but I seem to recall a sensation of burning against my chest in that moment. I grabbed the Six of Swords and flung it violently to the ground. Message received, I snarled silently, in my head, at the evil omen, talisman of loss, harbinger of death. Now fuck you, I want nothing more to do with you. And I stomped away, leaving the card face-down against the curb, believing and not believing in its power, insanely lamenting my decision to pick it up, as though doing otherwise would have altered the continuum of time. There was no jolt of wonder here, just a craving for the anesthesia of unconsciousness. I returned to the hotel, told Rachel the story of the Six of Swords, turned my back on her in bed, and slept.

Top photo by Leeloo Thefirst