Thirty-four years ago today, on July 26, 1989, Louis Fulgoni, an accomplished visual artist and a great friend and comrade, died of complications from AIDS at the age of fifty-three. Raised on Staten Island, he had spent most of his adult life in Manhattan’s Chelsea neighborhood. In the 1980s, he was the art director and I was the editor at a small publishing business we operated out of a one-room office on Union Square. Last year, I joined with Michael McKee, who was Louis’s life partner, to launch a virtual retrospective, Louis Fulgoni: Memory + Legacy, exhibiting the rich body of artwork Louis left behind. This remembrance is excerpted from the retrospective site, in honor of a creative spirit eclipsed too soon.

About a week after Louis died, I found myself walking up Eighth Avenue, carrying his boxed ashes in a shopping bag. As a favor to Michael, I had picked up the bag from Redden’s Funeral Home on West 14th Street, one of a minority of New York morticians then willing to handle the remains of people with AIDS. I had never carried anyone’s cremains before. They were surprisingly heavy. Now and then on the way to deliver them to Michael, I shifted the bag from one arm to the other to ease the strain.

Although I was not quite thirty-two, I felt older that day. After dropping the ashes off, I stayed with Michael for a while. Then, to clear my head, I took a walk back over to the Union Square office that Louis and I had shared.

I kept the office for a while after Louis’s death, but it felt empty and vaguely haunted. In his absence, I was hesitant to rearrange the place, but neither could I bear working in a sarcophagus day after day. When the lease was up, I decided to move to a different building nearby. While cleaning things out for the move, I ran into one of the other tenants on our floor, Frank, a strikingly handsome sculptor about my age, who had an enviably steady stream of attractive women – perhaps models, perhaps not – coming in and out of his studio. The exact nature of their visits had been a regular topic of wicked speculation between Louis and me, in part because Frank introduced us to his wife one afternoon in the corridor.

He invited me in, for the first time in the several years we had been neighbors. Over coffee, I mentioned my girlfriend in passing. Frank nearly choked on his espresso. He fixed me with an incredulous stare.

“But. You’re not gay?” he blurted out. “I thought. You and Louis. I mean.”

“No,” I said. “We were just good friends and we enjoyed working together, that’s all.”

He looked down into his cup and started to apologize for prying. I told him not to worry, that it was a perfectly understandable assumption. But in truth, his mistake took me by surprise. I suddenly realized that many people were probably under the same impression about Louis and me. If they’re not lovers, our casual acquaintances and clients must have wondered, what the hell are they? But the more I thought about this, the more absurd it seemed. Why shouldn’t we be close? It was like suggesting that hetero men and women couldn’t be friends or colleagues unless they were fucking.

I thanked Frank for the coffee and walked back down the hallway to finish packing the remnants of Louis’s art supplies. I couldn’t bring myself to throw anything away.

Eventually, the grief of that awful time faded. I got married, started a family and went on to a new career. Michael remained active as a tenants’ rights advocate and, in his early eighties, he still is. He also embarked on a new relationship with a wonderful man who is now his husband.

Moving on, as we did, is of course a natural part of the grieving process. In some ways, it is the easy part. Remembering can be hard, but it is essential. That’s why Michael and I decided, early in the COVID pandemic, to start work on the virtual retrospective exhibition of Louis’s work that launched online in June of 2022. We had been discussing the idea of an exhibition off and on for thirty years but made scant progress. It’s difficult to say why it didn’t happen sooner. We both remain immersed in Louis’s work; his art fills the walls of Michael’s apartment – the same one in Chelsea where they lived together – and I have hung at least a dozen Fulgonis in four different abodes since 1989. But our love for these precious artifacts was never quite enough to propel the idea into action.

Finally, the onset of another pandemic, distinct from AIDS but carrying familiar echoes of inexorable loss, gave the project new urgency. So did the relentless passage of time. “I’m determined, before I kick the bucket, to have a retrospective,” Michael said.

Remembering can also be a reckoning. It was for me, as work on the exhibition proceeded. Despite our age gap – Louis was about twenty years my senior – it occurred to me that I had always considered him a peer. He certainly treated me that way. In many cases, an older partner naturally acts as a mentor to the younger one, passing on accumulated knowledge and experience. I did not cast Louis in that role, and he never overtly played it, because that would have been alien to his nature. But in hindsight I reazlied that he did, in fact, teach me many things. Most profoundly, he modeled a level of devotion to channeling creativity, to living the life of an artist, that was a revelation and an inspiration.

Altruistically, through the exhibition, I wanted more of the world to feel, know and remember that devotion through his work. Selfishly, I was seizing the opportunity for a final, long-overdue creative collaboration with him, which the retrospective, in a certain sense, provided.

Thirty-four years is a long time but Louis is still sorely missed, and that is as it should be. In the 1980s, AIDS activists rightly proclaimed that silence about the crisis equaled death. For Louis Fulgoni and all those who perished before their time decades ago, death equals silence only if they are forgotten.

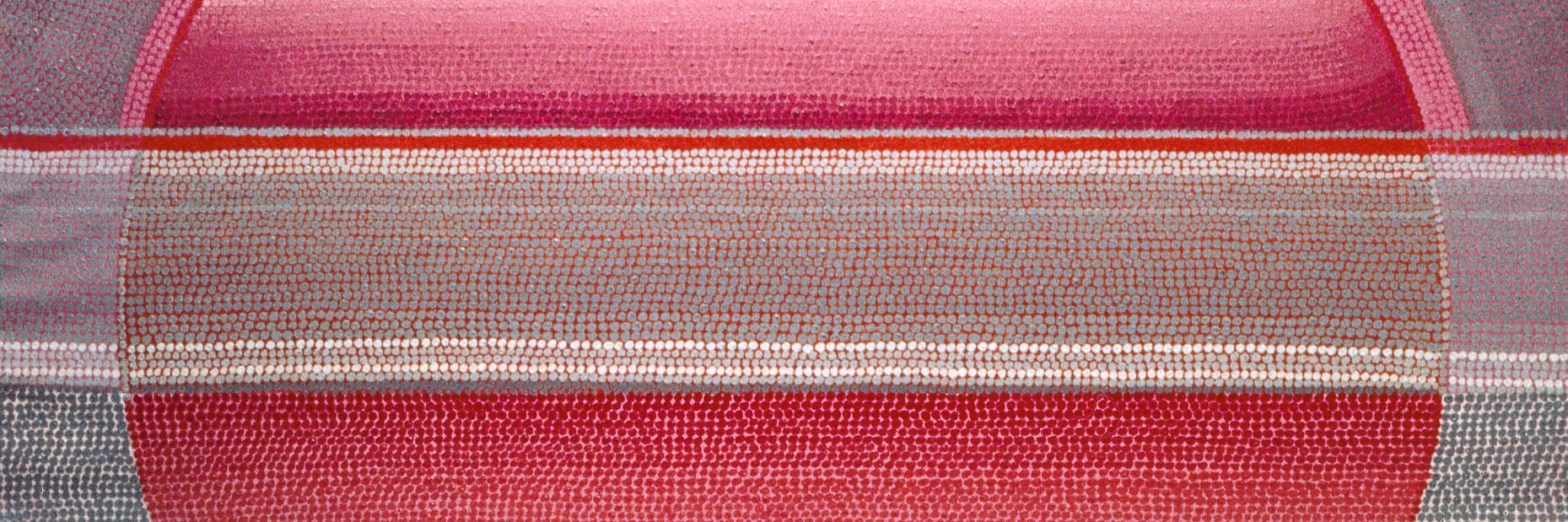

At top: Detail from an untitled painting, acrylic on canvas, late 1970s.

The full text of “Art of Memory” appears starting here on the Fulgoni retrospective site.