Roger and Maria Markovics on the winding road to tenants’ rights.

Ten Bucks I owe you?

Ten Bucks you say is due?

Well that’s Ten Bucks more’n I’ll pay you

Till you fix this house up new.

– “Ballad of the Landlord,” Langston Hughes, 1940.

The ground-floor office of United Tenants of Albany was tucked away on a corner of Columbia Street, down the hill and around the corner from the New York State Capitol and Albany City Hall. I had no idea what to expect as I opened the front door and stepped inside.

It was September 1977 and I had just started my junior year at the Albany campus of the State University of New York. For the first two years, I had managed to coast on the strength of an emotionally scarring but academically rigorous education in strict Catholic schools back home on Staten Island. Unleashed and unsupervised amid the freewheeling environment of college life in the 1970s, academics were the last thing on my mind.

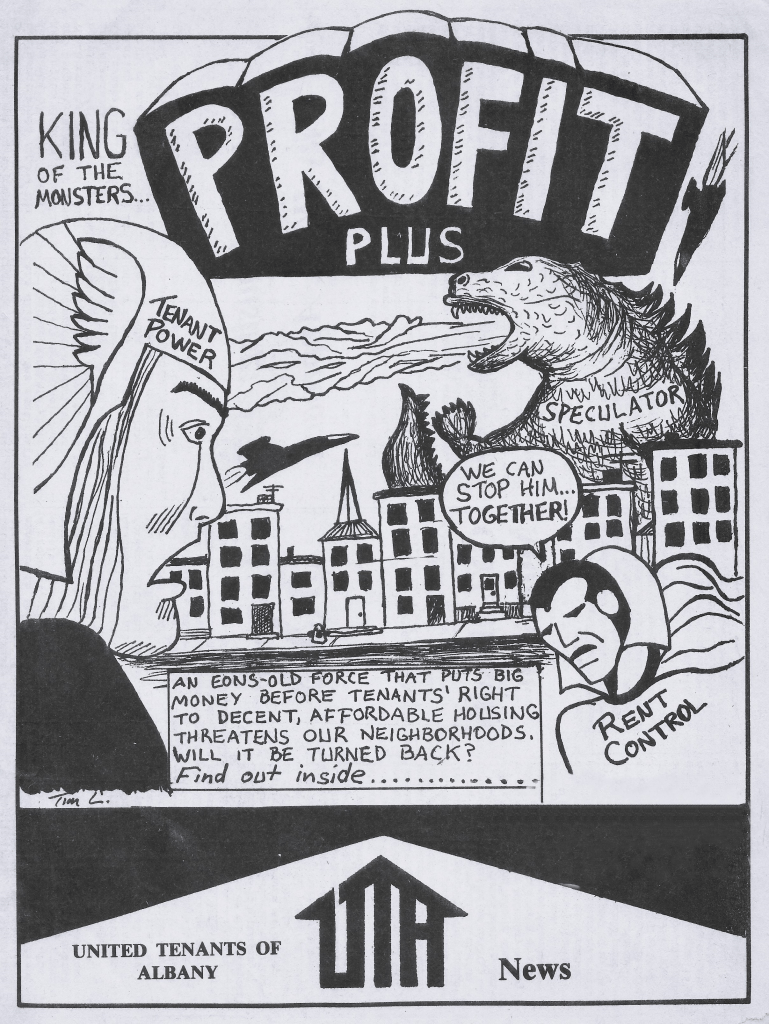

By now, though, I was beginning to feel the pressure of institutional requirements and expectations. In an attempt to score at least a couple of easy credits that semester, I had seized upon one of the “community service” courses listed in the SUNY catalogue. The two-credit, pass/fail classes were essentially unpaid internships at non-profits in the Capital District. For reasons I don’t quite recall, but possibly because I had just moved off campus into a ramshackle apartment on State Street with two friends, I selected United Tenants of Albany – UTA – from the list.

Having signed up for the internship, I still had to be interviewed. This was the purpose of my trip to the UTA office on that September day. When I walked in, I found a front room furnished with several mismatched desks. They were piled with newspapers, manila folders and telephone message pads. Two or three staffers were sitting there, deeply engaged in phone conversations. One of them, a youthful, wiry man with tousled dark hair, motioned for me to take a seat until he was done. After a few minutes, he hung up, put his stocking feet on the desk and introduced himself as Roger Markovics.

Roger explained that he and his wife, Maria, were UTA’s co-founders and coordinators. Maria was out at a tenant meeting, Roger said, so he would be interviewing me. It was really more of a casual conversation, during which he filled me in on the basic mission of the organization: securing tenants’ rights to decent and affordable housing in the inner-city neighborhoods of Albany. I assume he was also sizing me up as a potential asset or liability, because (as Maria had told me bluntly in a brief phone call setting up the interview) student volunteers could be either one.

In the end, I somehow passed muster. Roger and I agreed on the hours I would work two days a week, and I thanked him and left. The late summer sun was dazzling for a moment as I emerged back onto Columbia Street. Then I turned and strode up the hill toward the bus stop. I felt an incipient sense of purpose that was both exciting and, to a young slacker like me, unfamiliar.

Lifelong partnership

As it turned out, Roger and Maria Markovics had an enormous impact on my life, and we’ve stayed in touch over the years. Although they are now retired, UTA goes on, fifty years after its official founding – a milestone to be celebrated on September 21, 2023 at the Albany Labor Temple. I recently spoke with the couple at length about how their remarkable lifelong partnership came about, and what has sustained them over the long haul.

Indeed, by the time I crossed the threshold of the UTA office in 1977, Roger and Maria, then in their early thirties, had been working in Albany for eight years. They had also been married since 1970. I soon realized that, in many ways, their life together and their work together were indistinguishable.

This is not to say that they were, or are, the same person. Far from it. Where Roger is soft-spoken but often intensely serious, Maria is voluble and quick to laugh – frequently at her husband’s foibles, like his habitual lateness. Still, they share some important qualities. After all, they have now been married for fifty-three years and worked side by side for most of that time. Both Roger and Maria were born into politically moderate and religiously devout Catholic families at the end of the Second World War. And both, like so many in their generation, were profoundly influenced by the upheavals of the 1960s. Unlike many other baby boomers, however, they never abandoned the radical politics that they acquired back then.

Patriotic and religious roots

Maria – born Maria Mazzolini – was raised in the university town of Ann Arbor, Michigan. Her father was an immigrant from Tuscany, and all her grandparents were born in Italy. Maria described her father as a “super-Catholic” who prayed the rosary every night after dinner in May and October, the months designated by the Church for prayers to the Virgin Mary. Her mother was less zealous but still an observant Catholic. Although Maria’s parents were Democrats, they weren’t very politically engaged. “Politics were not a big issue in my growing up,” Maria recalled. “But I would say, from my father’s perspective, religion was.”

Roger’s parents, also practicing Catholics, were Hungarian-Americans who lived in the Hudson Valley town of Poughkeepsie, New York. His mother was a registered Democrat, his father a Republican. According to Roger, his “very patriotic” father was outraged by the revelations of President Richard Nixon’s treachery in the Watergate scandal, “but he probably still voted Republican.” Roger said his parents often joked that their votes cancelled each other out. But like Maria’s mother and father, they were not especially partisan. “They were very humanistic in terms of their take on life,” Roger said. “Their political affiliations were not big things.”

Roger and Maria did have somewhat divergent experiences in their school days. Roger went to public elementary and high schools in Poughkeepsie, while Maria attended a Catholic school in Ann Arbor, Saint Thomas the Apostle, from first through twelfth grade. Even though it was not as regimented as most parochial schools of that era – for example, students were not required to wear uniforms – Maria said she “tried desperately in my high school years to get out of there.” She didn’t manage to escape from Saint Thomas but afterwards enrolled as an undergraduate at the University of Michigan, a large public institution. If her family could have afforded it, Maria would have gone to Marygrove, a Catholic college in Detroit. “My life would have been completely different,” she said, sounding like someone who had dodged a bullet.

Radicalized in the ’60s

Of course, “U of M,” as everyone in Ann Arbor called it, not only affected the direction of Maria’s life; it had a massive impact on the entire local community. With nearly 33,000 students out of the city’s total population of about 100,000 as of 1970, the university was an economic anchor. In fact, Maria’s father worked as a cook at the Michigan Union cafeteria on campus, after her family closed a bar and restaurant they had owned a few blocks away.

U of M was also, crucially, a nucleus of latent activism. As the sixties progressed, it would explode into cutting-edge political protest for peace, civil rights and economic justice. Maria started classes there in 1963. “By sixty-five, the whole campus had changed,” she remembered. “People who I knew had pledged sororities in sixty-three were denying it in sixty-five.”

Dissent accelerated rapidly at colleges and universities across the United States in those years, but Ann Arbor was a bellwether. “Some campuses were later to catch up. U of M was early on,” Maria said. It was, for instance, the operating base for most of the leadership of Students for a Democratic Society, which agitated against the Vietnam war and for participatory democracy. U of M alumnus Tom Hayden was the principal author of the Port Huron statement, a radical manifesto that launched SDS in 1962. By the mid-sixties, teach-ins and demonstrations were ubiquitous on the Ann Arbor campus.

Like thousands of her fellow students, Maria was radicalized by these events. In the summer of 1966, she flexed her independence, taking a job with a federally funded children’s recreation program at a public housing project in Brooklyn, New York. But in her final year as an undergraduate, she developed severe symptoms of anxiety, which forced her to take time off before pursuing graduate studies. Feeling more secure after a year at home with her parents and her younger sister, she enrolled in the graduate School of Social Work at U of M in the fall of 1968.

Evolving politics

Meanwhile, several hundred miles east in New York State, Roger had made a different kind of transition – from his public high school in Poughkeepsie to Siena College, a small Catholic institution just outside Albany. More religious than his parents and three siblings, he had applied for admission to several Catholic universities. He received modest scholarship offers from Fordham and Georgetown, but a far more generous one from Siena. Financial considerations “tipped the scale” for his family, Roger recalled; he accepted that better offer, even though Siena was last on his wish list.

Like Maria, Roger started undergraduate classes in the fall of 1963. He also joined Siena College’s ROTC program. “This was before the Vietnam war heated up,” he noted, adding that he was firmly anti-communist at the time. (Just seven years earlier, the Soviet Union had crushed the nascent 1956 revolution in Hungary, where his grandparents were born.) But Roger quickly became disillusioned with ROTC and campus life in general at Siena. He began to question his own politics and, as he put it, his concept of “what it means to be Catholic.”

Siena was a Franciscan school ostensibly steeped in an intellectual Catholic tradition of reason, humanity and social justice. Nevertheless, Roger found the college administration excessively controlling and paternalistic, and the religious instruction shallow. The ROTC program – in which he spent two years as his political outlook evolved – “gave me a distaste for everything in the military,” he said. Eventually, he got involved in campus protests, culminating in a controversial anti-ROTC demonstration at his class’s commencement ceremony in 1967. “At graduation time,” he said, “about a dozen of us maybe, we put on suits and ties to look respectable and protested. But it shocked a lot of people. That was the first time there was anything like that on the campus.”

After graduating from Siena, Roger took a detour from higher education. He spent a year as a VISTA worker: first in Detroit just after the long, hot summer of 1967, and then in a poor Appalachian community in east Tennessee. Established under the Johnson administration’s War on Poverty agenda in 1965, VISTA (short for Volunteers in Service to America) placed mostly young volunteers in local community organizations working on economic development, literacy, housing and other issues. The VISTA placement “changed my life,” Roger said. It prompted him to apply – just as Maria had done – to the graduate School of Social Work at U of M. He was accepted and arrived at the Ann Arbor campus at the start of the 1968-69 academic year.

And so Roger and Maria became classmates, though neither remembers for certain whether they were initially in any classes together. They would meet soon, however. In an intimation of their shared future, that meeting would happen in the middle of a rent strike.

Student tenants on strike

One factor that drew Roger and Maria to the School of Social Work at Ann Arbor in the first place (aside from its obvious proximity to home for Maria) was the school’s offering of courses in community organization and community development. These classes went beyond traditional training in casework and signified an emerging imperative for systemic social change. It was an approach that suited the tenor of the U of M campus in 1968. As anti-war and civil rights protests intensified, Roger said, there was a prevailing sense that “if you’re not part of the solution, you’re part of the problem.”

In early 1969, Ann Arbor students channeled that activist spirit into a campaign for improvements in the city’s rental housing stock. Exasperated by widespread, persistent code violations in Ann Arbor apartments, a cadre of U of M students formed a steering committee for a citywide rent strike. Their ultimate goal was to establish a tenants’ union that would engage in labor-style collective bargaining with major property owners, thereby boosting renters’ leverage.

Maria joined the steering committee early on. At one committee meeting, she was responsible for managing the selection of organizing teams composed of two students each. The teams would knock on apartment doors in hopes of recruiting more tenants to participate in the strike and withhold their rent. When Roger arrived at the meeting half an hour late, the teams had already paired up. Maria was the one person left who didn’t have a canvassing partner. After chiding Roger for his tardiness, she told him they might as well work together. Their relationship could only go uphill from there.

More than 1,500 tenants, most of them students, took part in the rent strike, which lasted for two years. While the strikers’ more radical goals proved untenable, many targeted landlords did improve maintenance in their buildings. The action also inspired similar strikes across the country and resulted in the founding of the Ann Arbor Tenants Union, which remains active today. On some level, too, the rent strike planted the seeds for the tenants union that emerged a few years later in New York State’s capital city. But first, Roger and Maria would have to take a winding road from Ann Arbor to Albany.

“Plan on going to jail”

By 1968, Roger had overcome his adolescent flirtations with conservatism, anti-communism and the ROTC. In the fall of that year, just as he was entering graduate school at the U of M, he declared himself a conscientious objector to the war in Vietnam. Called before his hometown draft board in Poughkeepsie, he said his stance was based on both religious and moral principles. After deliberating, the board granted him “I-A-O” status under the Selective Service law. This designation meant that he could be drafted into the military but would serve in a non-combatant role. “I was hoping to be a medic,” Roger said. When he received a draft notice in the spring of 1969, however, he went further, deciding to refuse military service altogether: “I just said, ‘I’m not gonna go.’ I guess it had just been building up in me.”

A key event in Roger’s evolution into non-violent resistance at Siena was a discussion that he and several classmates had with two college-age volunteers from the Catholic Worker – the Catholic socialist and pacifist movement founded by Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin in New York in the 1930s. Roger remembered thinking: “They were guys just like us and they dropped out of Catholic colleges to work in the Bowery.” When they talked about Vietnam, the two simply said they were not cooperating with their draft boards and expected to go to jail, not to Canada.

Roger’s evolution meant that he had to reapply to the draft board for full conscientious objector status, classified as “I-O” by the Selective Service. If the board approved his request, he would have to do two years of alternative civilian service in lieu of military duty. But first, he’d need to clear a high bar of justification, and approval was far from certain. If the system turned him down and he still refused to serve, even as a non-combatant, he would face prosecution as a draft evader and, most likely, a five-year sentence in federal prison.

By this time, Roger and Maria were a bona fide couple. They travelled together to New York State for the new hearing with his draft board. Before going to Poughkeepsie, though, they made a detour to the New York City office of the American Civil Liberties Union. Draft counselors in Michigan had directed them there for further guidance. ACLU lawyers said Roger’s background as a VISTA volunteer and former ROTC candidate added interesting wrinkles to his case. Still, the likely outcome was grim. “You’re probably going to get convicted,” one of the lawyers told Roger. “Plan on going to jail.”

Proposal on the Taconic

While they were in Manhattan, the couple also visited a convicted draft resister who had just been released from federal prison after three and a half years. The young man agreed to meet with them, Roger said, but he seemed distant and distracted. After that visit and the dismal consultation at the ACLU, Roger and Maria took what must have been a somber drive north on the Taconic State Parkway toward Poughkeepsie and the draft board.

As they talked in the car about their future, Roger blurted out, “Do you ever think about marriage? I think we could do that, don’t you?” Only after he said it did he realize what he had proposed. When Maria said yes, he started to backtrack, worried about how difficult it would be for her to wait several years if he were incarcerated. They both remembered Maria’s definitive response: “You don’t know how strong I am.”

Maria’s strength, and Roger’s, would be tested in the ensuing months. The Poughkeepsie draft board denied his renewed conscientious-objector application, leading to two appeals, first at the state-level draft board (which also rejected it) and then before a federal panel. On January 3, 1970, while they were still anxiously awaiting a decision, Roger and Maria were married in Ann Arbor. Soon after that, a letter arrived from the Selective Service office in Washington, DC. It said the final appeal in Roger’s case was successful, and the federal panel had approved his I-O status after all. “I guess they were just overwhelmed with applications and appeals at that point,” he said in hindsight.

Surprised and overjoyed by the news, Roger and Maria no longer had to worry about a knock on the door signaling his impending arrest. All they had to do now was figure out where he would perform his alternative service.

Soft landing at Providence House

The Selective Service bureau offered listings for conscientious objectors to fill outside the military, but Roger and Maria found them uninspiring. They viewed Roger’s placement as an opportunity for a new start after receiving their social work credentials, but the listings “were mostly hospital orderly jobs,” Roger said. “We wanted to work on some kind of social change.”

Their break came through the priest from Siena College who married them – a young “street priest” who had established a crisis intervention center named Providence House in the South End of Albany. The center had a job opening, and Roger and Maria applied for it together. After meeting and talking to the couple, the priest agreed to hire them and approached the state draft board to approve the placement as Roger’s alternative service. The board consented. Roger and Maria commenced working at Providence House in August 1970, splitting the modest salary between them. “So that’s how we got to Albany,” Maria said. But getting there was just the beginning.

As Roger and Maria embarked on casework with sometimes desperate clients, they saw how challenging daily life could be for poor people and residents of color in the state capital. At the time, Albany’s population – roughly the same as Ann Arbor’s – was in decline. While its economy was sustained by the presence of the state government, it suffered the effects of white flight to surrounding suburban areas, exacerbated by financial redlining and disinvestment. The city’s most depressed neighborhoods, including the South End, Arbor Hill and West Hill, were home to majority African-American populations in what was, and remains, a highly segregated northern city.

Albany was also in the vice grip of a housing crunch that so-called urban renewal projects only aggravated. The worst offense was the demolition of an entire downtown neighborhood to make way for the South Mall, the massive, marble-clad state office complex that displaced at least seven thousand residents from their homes and destroyed four hundred viable, mostly small, businesses.

It soon became clear to Roger and Maria that City Hall was decidedly part of the problem, not the solution, to many of Albany’s social ills. The mayor, Erastus Corning, had been in office for three decades, first elected more than a year before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. His entrenched administration was an old-fashioned Democratic machine operated by ward leaders and political allies who, to say the least, did not demonstrate impressive professional competence or expertise. “I think the head of public assistance was the mayor’s chauffeur,” Maria said. “It was pretty amazing, coming from a place like Ann Arbor especially. I thought, like wow, who are these people?”

From casework to organizing

In short order, Roger and Maria also realized that acute housing insecurity was at the root of many of their clients’ difficulties. “We were doing a lot of direct service in the beginning, and then we started talking to people, and housing became the issue,” Maria said. Under Corning, there “was not exactly a progressive approach to housing issues,” she added. It didn’t help that the head of Albany’s housing code enforcement bureau was a ward leader with no apparent background in the field, or that the city systematically failed to foreclose on tax-delinquent but politically connected slumlords.

“People kept coming in looking for apartments, and there weren’t any to rent,” Roger said. “So we kept telling them, ‘Since you can’t find anything better than where you are, what can we do to improve your apartment?’” That was when he and Maria turned from casework to organizing. They held meetings with groups of tenants whose apartments had code violations, helping the tenants press their landlords and the city to follow up with repairs, heating and other basic services.

Many of the residents dealing with substandard housing were also receiving public assistance, which brought its own challenges. Roger and Maria met and collaborated with Catherine Boddie, a welfare rights organizer working with tenants in Albany’s public housing projects. Boddie was one of several community organizers who had been active on housing and welfare issues in Albany for years before Roger and Maria arrived. “We got really introduced to community life through them,” Roger acknowledged.

Among the other organizers on the scene were Jack Mayer from Trinity Institution, a social services agency, and Olivia Rorie, an outspoken activist pushing for better housing with African-American pastors and congregations in the South End. There were also the Brothers, a group composed of young Black men who worked on civil rights, employment and neighborhood quality-of-life improvements. The work of these individuals and groups reinforced Roger and Maria’s resolve to help tenants fight for their rights. Over time, they also connected with tenants from the community – Cat Hoke, Cliff Cutler, Cynthia Temple and more – who would later work at the UTA office. “There was a growing network of people that we met who spurred us on,” Roger said. “These weren’t things we did alone, obviously.”

In Albany to stay

The couple continued working out of Providence House for a few years, but in 1973 they incorporated United Tenants of Albany as a separate 501(c)3 nonprofit organization. Although the Albany Diocese kept paying their salary through its Catholic Charities office, the incorporation gave Roger and Maria some additional leeway in the tactics they could adopt.

In fact, a diocesan lawyer helped them complete the application process for nonprofit status, partly because it would allow the Church to legitimately say UTA was independent in case of controversy. At the same time, Sister Serena, the head of the Catholic Charities office, remained an unwavering advocate for their organizing work. “She was cool,” Maria recalled. “She looked like your traditional old skinny nun, but she was a dynamo.”

The diocese would continue paying Roger and Maria until their joint retirement in 2016. “Roger and I were employed by Catholic Charities, but United Tenants was separately incorporated. It’s always been a very unusual relationship,” Maria said. Added Roger: “The unspoken agreement was that we would raise all the money for the organizing.”

By the mid-1970s, they were gaining local media attention with events like a “Code Violator of the Month” award designed to shine a spotlight on negligent property owners and the city officials who enabled them. (The city’s Code Enforcement Bureau went on to receive UTA’s “Code Violator of the Year” prize.) UTA also started working in coalition with other groups such as the League of Women Voters and Albany’s burgeoning neighborhood associations, which posed a direct challenge to the previously unquestioned power of local ward leaders. Progress was slow, and new patterns of gentrification and displacement faced UTA, its partners and tenants themselves as the decade progressed. But Roger and Maria had hit their stride. Albany was home, and they were there to stay.

A force for good

When I first crossed paths with UTA forty-six years ago, it was already well recognized – by the media, City Hall, landlords and tenants alike – as an organization with genuine political clout. By then, Roger and Maria had hired several tenant counselors and organizers with grants from the Campaign for Human Development and federal funding from VISTA and CETA, the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act program. When federal anti-poverty funding later scaled back drastically in the Reagan era, UTA would fill the gap with grants from the New York State Neighborhood Preservation Companies program, among other sources.

During my first weeks as a student intern at the tenant office, I mainly tried to stay out of the way. And yet, the atmosphere was warm and welcoming. Eventually, with support from the staff and a crash course in landlord-tenant rules and regulations, I felt confident enough to do more than take phone messages and pick up documents from the Albany Legal Aid Society office down the block. Among other responsibilities, I answered calls and offered basic guidance and referrals to tenants calling for assistance, but only after checking with more experienced hands in the office first.

Having acquired a small amount of know-how, I came back the next semester for another stint as an intern. Eventually, UTA hired me to fill a full-time CETA position. I stayed for a year, working extensively on newsletters, press releases and other UTA communications, which turned out to be my niche with the organization. I moved back to New York City in late 1980 to work on communications at the New York State Tenant and Neighborhood Coalition, a statewide alliance organizing and lobbying for fair housing laws and policies. (UTA was then, and remains today, a member of the coalition, now called New York State Tenants & Neighbors.) From there, I embarked on my four-decade career as a full-time writer and editor, all of which stemmed directly from my youthful encounter with a married pair of radical Catholics in Albany.

There is some irony here, because as aimless as I felt before meeting and working with Roger and Maria, one thing was certain in my mind: I had no further use for the Church. Recovering from my experience in Catholic schools, I felt liberated at last from the indoctrination they had foisted upon my classmates and me.

In the 1960s, the nuns in my elementary school on Staten Island hailed from the Daughters of Divine Charity, an order founded in central Europe. They made few distinctions between communists, hippies and Satan incarnate. In the early seventies at my high school, an elderly Christian Brother – an Irishman who had spent years teaching in Spain – accosted our sophomore Spanish class with a diatribe about how the fascist dictator, Francisco Franco, had saved the Church from its godless adversaries. I didn’t know much, then, about the relative merits or evils of capitalism, communism or any other political or economic system. Still, I came of age in a period when the winds of social change were strong enough to permeate even those parochial classroom walls. I knew the moral universe had to be more complicated than my teachers let on.

Since then, of course, public revelations about the Catholic Church’s systemic problems have cast a long shadow. That shadow has reached Albany, most notably in the case of Howard Hubbard, the street priest who first took Roger and Maria Markovics on board at Providence House in 1970. Hubbard – who died in August at eighty-four – became Bishop of the Albany Diocese in 1977 and championed UTA unequivocally over the decades. In more recent years, he acknowledged his failure to report cases of child sexual abuse by other clerics and faced allegations that he, too, had been a perpetrator.

The prevalence of such cases among the Catholic clergy suggests, to me at least, the hypocrisy of the Church as a self-professed moral authority. The community that coalesced around UTA, on the other hand, always struck me as an unambiguous force for good, and an understated one. Roger and Maria Markovics have never worn their religious values on their sleeve but simply lived them.

In the tradition of the Catholic left, for more than a half-century, they have embodied a model of decency in action that aligns with the best of the religion’s professed aspirations: that the poor shall inherit the earth, that whatever you do to the least of my brothers and sisters, you do to me. Without ever really talking about it, they have been sustained by a vision of peace and justice rooted in the gospels. Like the Good Samaritan, they’ve refused to stand by in the face of human suffering, especially suffering caused by injustice and inequality that deprive people of the essential human need for shelter. I honestly don’t know of any other life’s work that could be more divine.

Photo at top, courtesy of Preservation League of NYS